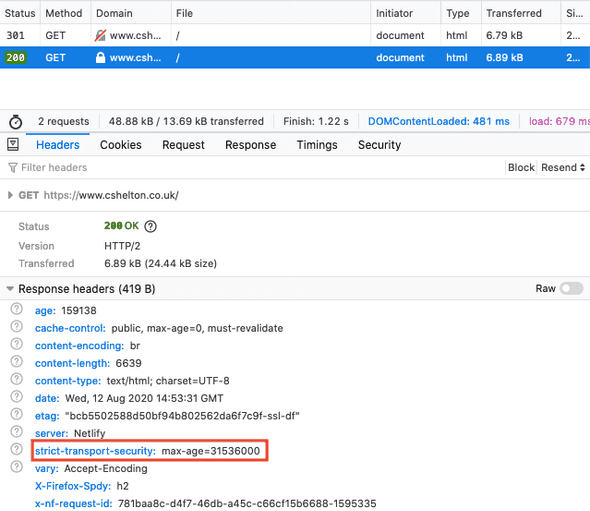

Published on August 19, 2020

Introduction

Netlify is a great platform for simple web hosting, which comes with a whole load of benefits, including a generous free plan, HTTPS out-of-the-box, and cool features like AWS Lambda integration and form submissions. I plan on writing a blog post specifically about Netlify, including how I use it and what benefits I get from it.

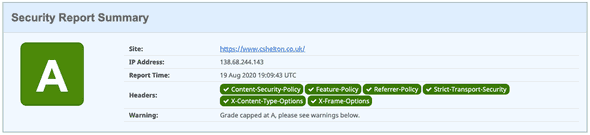

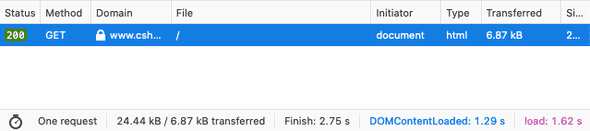

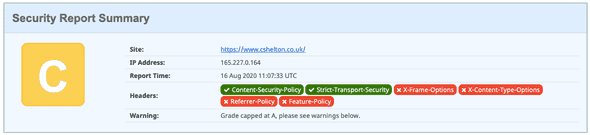

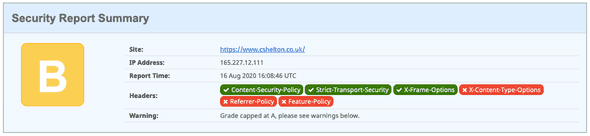

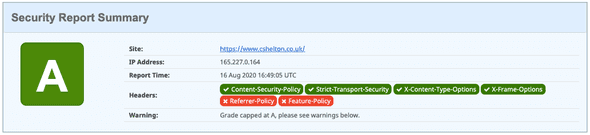

I was made aware, that by default, some HTTP Security Headers are not set by default when hosting a site on Netlify, and sure enough, for my Portfolio site, most were not set which resulted in a pretty poor rating on Security Headers:

As you can see above, the poor rating is due to Content Security Policy, X-Frame Options and other security headers not being setup or configured correctly. I was keen to fix these security issues, and blog my process.

Security Headers - what and why?

Security headers are instructions sent by the server in the HTTP response which inform the browser how to handle communication with it, specifically in a way which maximises the security of the communication.

It’s hard to talk about web security and not mention OWASP — the Open Web Application Security Project. If you’re not familiar with OWASP, and you are involved in the technical aspects of web application development, regardless of technology, it is recommended you familiarise yourself with the guidelines to help you and your team build more resilient and secure applications.

Importantly, OWASP has a project specifically for providing guidance on securing web applications through the use of HTTP headers — the OWASP Secure Headers Project — which defines them as:

…HTTP response headers that your application can use to increase the security of your application. Once set, these HTTP response headers can restrict modern browsers from running into easily preventable vulnerabilities. The OWASP Secure Headers Project intends to raise awareness and use of these headers.

There are numerous security headers which can be sent by the server, but the most common, and ones which I’ll be focusing on are:

- HTTP Strict-Transport-Security (HSTS)

- Content-Security-Policy

- X-Frame-Options

- X-Content-Type-Options

- Referrer Policy

- Feature-Policy

Security Headers in Netlify

Netlify offers a couple of ways to set the headers for your site, as explained in the documentation.

The first way is by creating a netlify.toml configuration file, which is stored in the root of your repository, and configures settings related to your build and deployment, along with setting response headers and any environment variables.

The second way is by creating a _headers file, which is stored in the root of your repository, and is specific for configuring the headers for your site. Headers can be set either globally across the domain using /*, or for specific paths in your site using /skills-and-experience, for example, with the headers nested underneath.

Given I was only interested in configuring the headers for my site, I chose the latter approach, targeting the whole domain.

HTTP Strict-Transport-Security (HSTS)

The HSTS header sent by the server informs the browser that any requests made to a site must only be made using HTTPS. HSTS is not to be confused with HTTPS redirection, which is a configuration setting on the server which will force redirect any traffic made over HTTP to use HTTPS.

The instruction to always use HSTS is remembered by the browser after the initial request, so that the browser knows that any subsequent requests made to the server should never be made using HTTP, only HTTPS. The browser will automatically convert a request made over HTTP to use HTTPS. This instruction is not tied to the user’s browser session, and persists for as long as indicated in the header using the max-age directive (typically one year).

The server will always respond with the HSTS header, even if the browser has already received this instruction previously. This means that every time the user visits the site, the expiry date of the HSTS instruction stored by the browser is continually updated, ensuring that the user is protected for as long as possible with a reduced chance of the instruction ever expiring.

An Example Flow

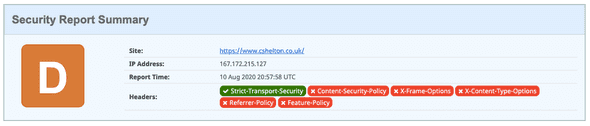

- The user accesses

http://www.cshelton.co.uk/for the very first time (note the use of HTTP, not HTTPS). - The browser has never received the HSTS header for this site before, so continues to send the request over HTTP.

- HTTPS redirection is setup on the server, which issues a

301 Moved PermanentlyHTTP response to the browser, with an updated location URL, so the browser can issue the request again, but using HTTPS:

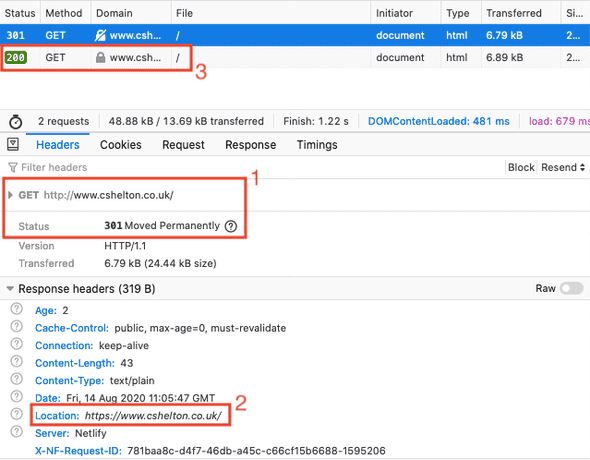

- The server responds to the now secure request with the page content, along with the HSTS header in the HTTP response:

- The browser stores the HSTS instruction to be used for subsequent requests.

- The user accesses the site again, or another page on the site, over HTTP.

- Before sending the request to the server over HTTP, the browser realises that it has an instruction to only send requests using HTTPS, so it automatically converts the request to use HTTPS and then submits it to the server, resulting in only one secure request being made:

Resolution

Fortunately, all Netlify apps are served over HTTPS and use HTTPS redirection by default, for no cost — this is an excellent move by Netlify 👍.

As can be seen above, HSTS is already in action on my site, configured automatically by Netlify, so I didn’t have to do any work here. Result!

Content-Security-Policy (CSP)

Now onto the first security header which has been flagged as missing — Content Security Policy.

The CSP header is an important one to help guard against Cross-Site Scripting (XSS) attacks. XSS is recognised by OWASP as being one of the top 10 most critical security risks to web applications, so it’s key to be aware of this attack and how to guard against it.

One way to help guard against XSS is to make use of the CSP header, and make sure it’s configured to be as strict as possible. A CSP is a way for a web server to tell the browser what kind of content is allowed for a site, and if that content is hosted externally, where is it allowed to come from. A CSP is defined by a set of semi-colon delimitered policy directives, where a policy directive takes the form <directive name> <directive value>.

There are many directives which help restrict content, but some of the most common are:

default-src- Acts as a fall back source for any directives which haven’t been specified.script-src- Restricts how JavaScript can be used on the site.style-src- Restricts how CSS can be used on the site.img-src- Restricts how images can be used on the site.

For each directive included, the value must be supplied, which defines how that content can be included and used. Typically, most content will come from your own domain, like external JS files, style sheets and images, and for that, you can specify your own domain. You may then provide additional domains for whitelisting specific content, like Google Analytics scripts for example, or styles from a Content Delivery Network (CDN). It’s important to note that this also applies to inline <script> and <style> tags — unless explicitly whitelisted using the unsafe-inline value, inline content will be blocked by default.

It’s not difficult to see from the directives above how a strict CSP can help guard against XSS attacks — by specifying exactly where content should come from, specifically script content, and how it should be executed, an attempt to load in a script tag entered maliciously by an attacker can be prevented by the browser.

Consider carefully whether to use the unsafe-inline value, as this begins to negate the benefit of having the CSP to guard against XSS attacks. You may find you can extract your inline scripts and styles to external files instead, unless you are making use of patterns like critical CSS, where that’s not possible, and you will have to look into safer approaches, like hashing or using a nonce value. Troy Hunt wrote a good article about the safer alternatives to using unsafe-inline — it’s definitely worth a read.

Ultimately, unless you have a very basic application, configuring the CSP header, and doing it properly, is not a trivial task. This was my first time implementing one, and it does feel like there’s a certain art to it. There are many ways to set the values of the policy directives, including using wildcards and specifying the allowed scheme and port. I would recommend reading up further on CSP before implementing your own.

Resolution

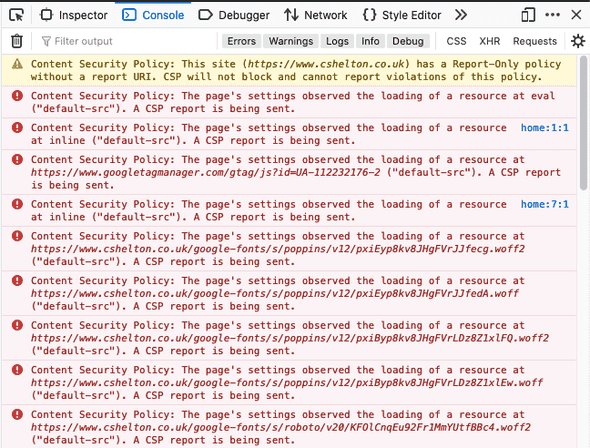

Something very useful to know when configuring your CSP, is the Content-Security-Policy-Report-Only header, which acts just like the Content-Security-Policy header, only it reports back what issues you’d be having with your CSP, rather than actually applying it. This makes testing much easier and safer against a live site, if that’s all you have (as I do).

I first added just the default-src directive with my own domain as the value, pushed my changes, and then checked the browser console:

Lots of errors… good? It shows my new header is working, but is only reporting the errors to me, so I can see what changes I need to make.

Anyway, after a lot of experimentation, my final CSP header looks like this:

/*

Content-Security-Policy: default-src https://*.cshelton.co.uk; script-src https://*.cshelton.co.uk https://www.googletagmanager.com https://www.google-analytics.com 'unsafe-inline'; style-src 'unsafe-inline'; img-src data: https://*.cshelton.co.uk www.google-analytics.com

A few things to note:

- I have set my

default-srcdirective tohttps://*.cshelton.co.uk, so that the fallback for any omitted directive is to only allow the content to come from my domain, over HTTPS. - As well as whitelisting my own domain in the

script-srcdirective, I am permitting script content to be loaded specifically for Google Analytics to work. I am also, unfortunately, permitting scripts to be loaded inline, which is a side effect of using Gatsby, which introduces inline script tags in my pages. - I am also permitting style content to be loaded inline, another side effect of using CSS-in-JS and Gatsby, which inserts my page styles into the

<head>of each page, for quicker page load times. - As well as whitelisting my own domain in the

img-srcdirective, I am also permitting images to be loaded using thedatascheme, which is used to embed images using a base-64 string, and from Google Analytics, which is required.

As noted above, my CSP is certainly not as strong as I’d like, but I am somewhat limited to the way Gatsby works, and ultimately, my site is purely static, with no user content other than my own, so I’m not too concerned. The gatsby-plugin-csp seemed like an option to use hash values instead of unsafe-inline, but there is a known compatibility issue which prevents me from using it. I will be keeping an eye on any improvements to Gatsby and its plugins which might allow me to tighten up my policies in the future.

For now anyway, I do get some limited protection with this CSP header in place, and checking my site against Security Headers again, I can see I have a ✅ for CSP, and a slightly improved rating — getting there!

X-Frame-Options (XFO)

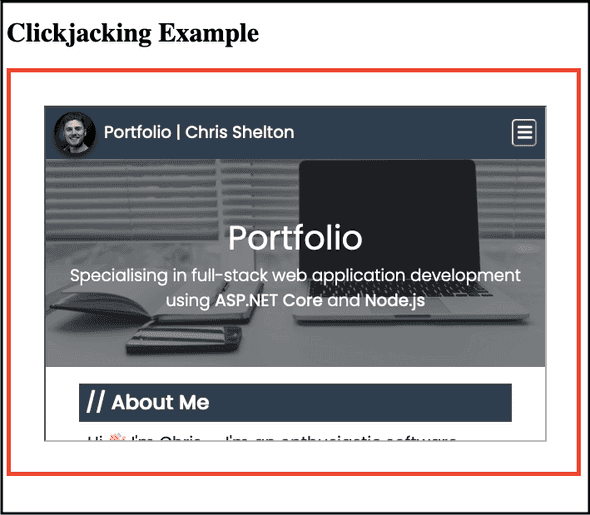

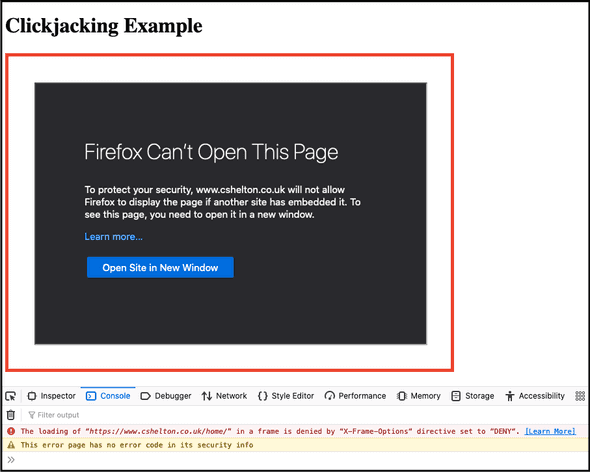

The <iframe> HTML element allows a site to embed another site’s content within it, much like in the screenshot below, where I created a basic test page with an <iframe> pointing to my Portfolio site:

It has its uses, but the <iframe> tag can be used to facilitate a malicious Clickjacking attack, where an invisible <iframe> is placed in front of a malicious site, which tricks the user into clicking on a button within it, which has most likely rendered a genuine site which the user is already logged into, causing the user to perform an authenticated action unknowingly.

I highly recommend reading Troy Hunt’s blog post on Clickjacking, where he walks through an example and talks in more detail about the implications of the attack.

So now onto the XFO header, which is a fairly simple one (compared to CSP at least) — this header instructs the browser what to do when a site is being rendered into an <iframe>.

There are two supported directives:

DENY- Do not allow the site to be loaded into an<iframe>.SAMEORIGIN- Only allow the site to be loaded into an<iframe>from within a page on that same site.

Resolution

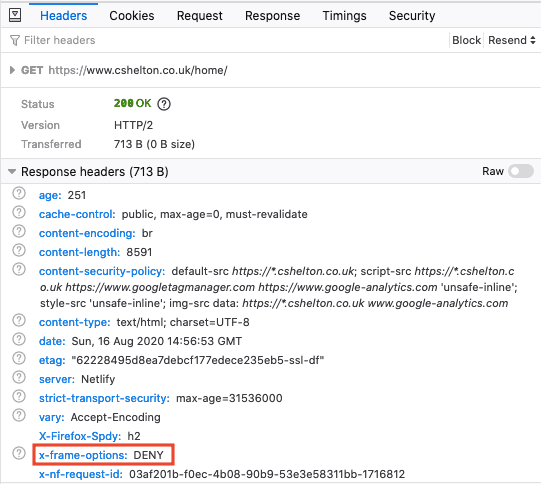

I have no requirement for any site, not even my own, to be able to render my site within an <iframe>, so I chose the DENY directive here.

/*

Content-Security-Policy: default-src https://*.cshelton.co.uk; script-src https://*.cshelton.co.uk https://www.googletagmanager.com https://www.google-analytics.com 'unsafe-inline'; style-src 'unsafe-inline'; img-src data: https://*.cshelton.co.uk www.google-analytics.com

X-Frame-Options: DENY

After doing so, the <iframe> on my basic test site no longer works, and I can see a suitable error in the browser console:

And the XFO response header is visible in the network tab when trying to request the page:

Running my site through Security Headers yet again, the rating has improved and I now have a ✅ against X-Frame-Options:

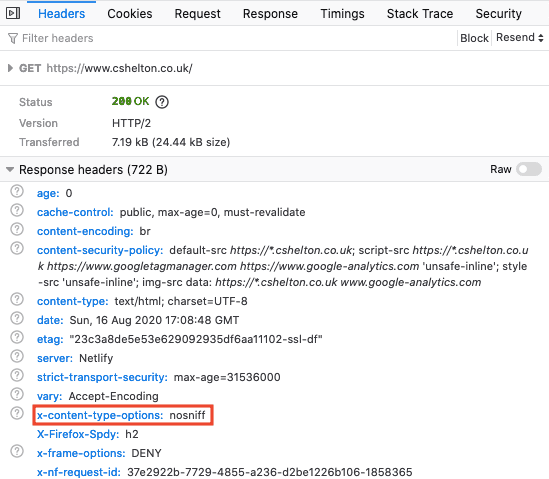

X-Content-Type-Options

Next up is the X-Content-Type-Options header, which is one of the simplest to configure, and only has one possible directive — nosniff. This header instructs the browser not to do any MIME type sniffing, and instead, rely on the MIME type provided in the Content-Type header from the sever without changing it.

This helps prevent the browser from downloading a potentially malicious file without the user’s consent, AKA a “Drive-by download”. It also helps ensure that files being downloaded with consent, remain the type specified, without, for example, the browser changing them to an executable.

Resolution

I added the X-Content-Type-Options header to my _headers file:

/*

Content-Security-Policy: default-src https://*.cshelton.co.uk; script-src https://*.cshelton.co.uk https://www.googletagmanager.com https://www.google-analytics.com 'unsafe-inline'; style-src 'unsafe-inline'; img-src data: https://*.cshelton.co.uk www.google-analytics.com

X-Frame-Options: DENY

X-Content-Type-Options: nosniff

And observed that it is now being sent in the response headers:

Security Headers now shows an A rating along with a ✅ against X-Content-Type-Options:

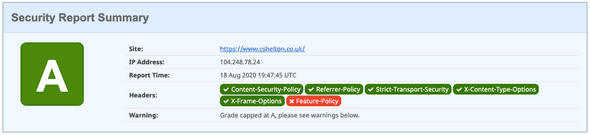

As indicated in the summary above, I have reached my maximum rating of an A now, with an A+ unattainable due to my use of unsafe-inline above. I could stop here, but for completeness, I thought I’d see it through to add in the remaining headers.

Referrer Policy

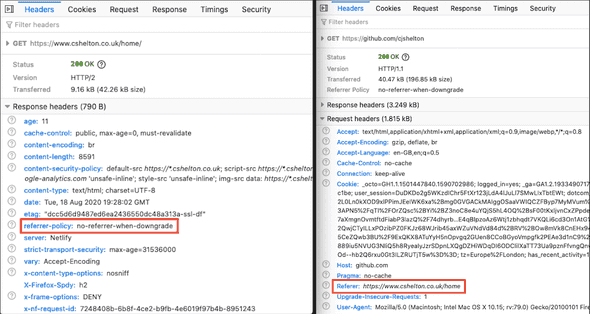

When navigating from one site to another, say from https://www.cshelton.co.uk/ to https://github.com/, the browser sends a Referer request header which can provide some basic information about where the request originated from. How much information is sent in this header can be configured through the origin’s Referrer Policy response header.

There are a variety of directives to choose from, ranging from no-referrer, which sends no information, to unsafe-url, which always sends the origin, path and query string, and as indicated in the name, is not recommended for use.

Resolution

I have no reason to hide any referrer information, so I opted for the no-referrer-when-downgrade directive. This is the default if not specified, and ensures that referrer information is only sent when navigating to a destination which uses the same or a stronger security protocol (i.e. HTTP to HTTP, HTTPS to HTTPS and HTTP to HTTPS). Since my Portfolio site is setup to always use HTTPS, referrer information will only be sent when navigating to other sites using HTTPS.

I added the Referrer-Policy header to my _headers file:

/*

Content-Security-Policy: default-src https://*.cshelton.co.uk; script-src https://*.cshelton.co.uk https://www.googletagmanager.com https://www.google-analytics.com 'unsafe-inline'; style-src 'unsafe-inline'; img-src data: https://*.cshelton.co.uk www.google-analytics.com

X-Frame-Options: DENY

X-Content-Type-Options: nosniff

Referrer-Policy: no-referrer-when-downgrade

Below shows the Referrer Policy response header set on my Portfolio site, and the Referer request header set when navigating away to GitHub:

Checking Security Headers again, it shows a ✅ against Referrer-Policy, and the rating remains at an A:

Feature Policy

And finally, the last header to address in order to get a ✅ across the board is the Feature Policy.

As browsers and the web evolve, the features available to the developer in the browser when building web applications become richer. For example, modern browsers permit the use of the host machine’s webcam and microphone, and access to the accelerometer and geolocation data, to name a few.

The Feature Policy header is a way of defining what features are allowed to be used on a site, and by any <iframe> elements on the page. For each feature, there is a corresponding directive which can be configured in the header, similar to the CSP. According to MDN, this header is still in an experimental state, and so the directives are subject to change. For an up-to-date list of the available directives, it is worth checking out the MDN page.

Resolution

Given this header is experimental, it’s difficult to know how to configure it, but I landed on the following, choosing to prevent the use of any features which might pose a security risk on my site:

/*

Content-Security-Policy: default-src https://*.cshelton.co.uk; script-src https://*.cshelton.co.uk https://www.googletagmanager.com https://www.google-analytics.com 'unsafe-inline'; style-src 'unsafe-inline'; img-src data: https://*.cshelton.co.uk www.google-analytics.com

X-Frame-Options: DENY

X-Content-Type-Options: nosniff

Referrer-Policy: no-referrer-when-downgrade

Feature-Policy: camera 'none'; display-capture 'none'; document-domain 'none'; geolocation 'none'; microphone 'none'; payment 'none'; usb 'none'

And that’s it! Security Headers shows a ✅ against Feature-Policy, completing the headers I set out to configure: